Food systems for human, economic & planetary health

CCI / CAFSA policy brief for the Food Systems Summit +4 stocktake, ongoing now in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. The core message is: food systems can be the everyday engine for sustainable development.

A CCI Blue Note policy brief for the 2nd Food Systems Summit Stocktake (FSS+4) taking place in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Four years after the historic United Nations Food Systems Summit, there are many big questions looming about the future of food systems, globally, at regional and national levels, and in terms of what is available to people, locally, in their everyday lives. A few contextual insights are necessary to frame those big questions:

Industrial-scale processes, including finance, transportation, and logistics, have a greater influence on how human beings get food today than ever before.

A wicked polycrisis of climate disruption, shock supply chain disruptions linked to COVID and conflict, resurgent protectionism, and worsening income inequality, have pushed hunger to all-time highs.

Much of the transformative potential in our food systems is in the hands of smaller-scale actors, even subsistence communities, who are generally ignored by mainstream food policy and finance.

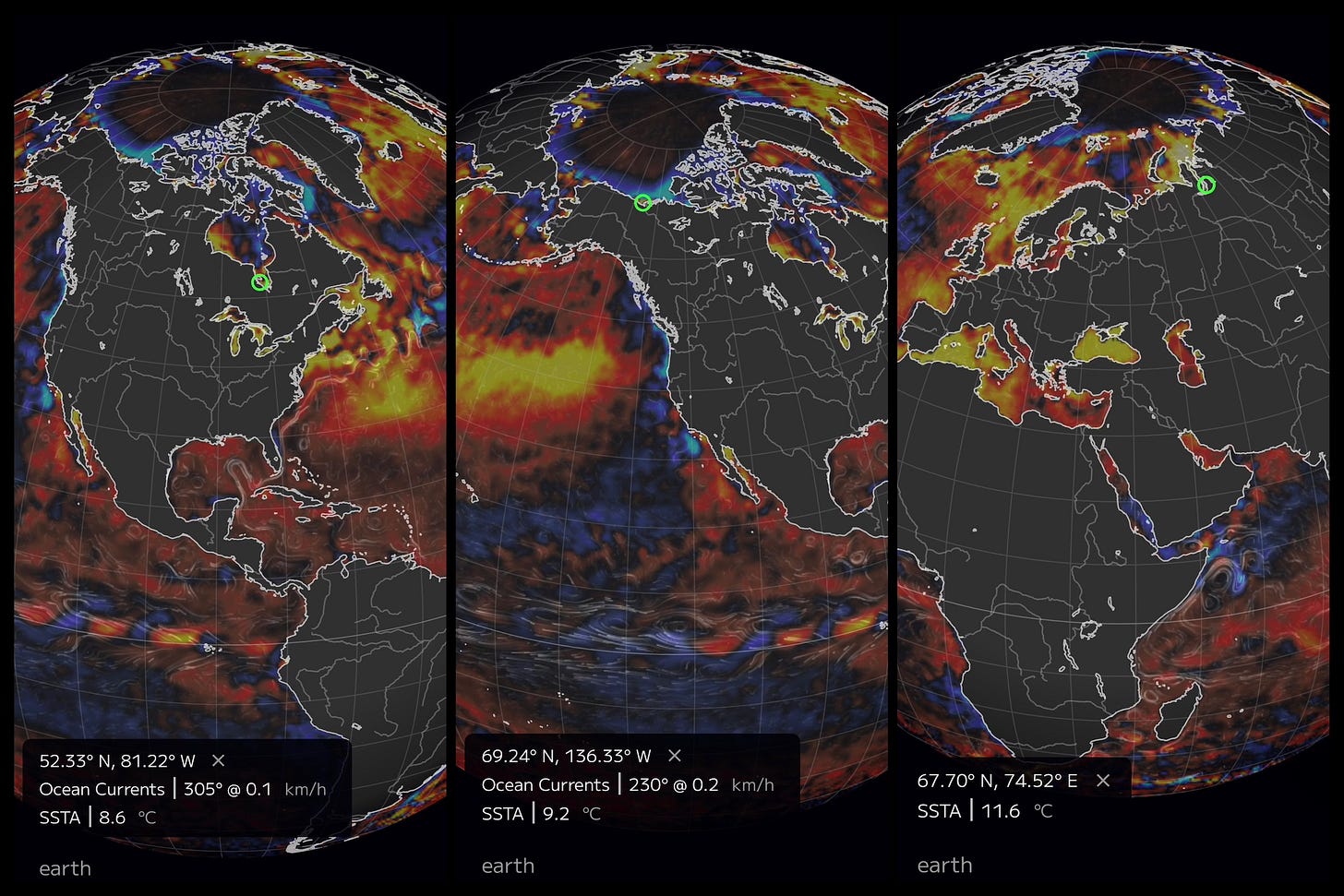

Earth system data—available not only to large institutions but also smallholders and communities—are essential for supporting the transition to climate-resilient, regenerative food production.

Planetary health is more of a concern than ever before, as we now see high-impact climate anomalies nearly all the time, including floods, droughts, storms, and rising sea levels.

The living reality of food systems at this moment is one of systemic stress, deepening inequality, and rising potential for breakdown. All discussions of what constitutes sustainable and resilience-building food systems investment and action must start from this insight.

If we look at each of the five points of context, which inform that overarching insight, we can see there are specific kinds of policy and investment that hold the greatest potential for moving the world onto a more humane, stabilizing, and value-building trajectory. Food systems can be levers for restoring nature, slowing and reversing global heating, building climate resilience, enhancing fiscal stability, and diversifying low-income, rural, and frontline economies.

The problem of industrialization

When agriculture adopts industrial methods, some things are lost and some gained. Where productive capacity, intermediary services, technological advances, and improved cost of capital, may all increase, the ability of producers to also be stewards of natural systems tends to decline. This is because industrial-scale agriculture has, until now, aimed at maximizing the value extracted from nature, not the value that can be put back or sustained by a healthy environment.

Industrial-scale value chains need to discover new levers for building value in real time and for the long term. Vertical integration may not be the future of industrial-scale food systems, as new methods and tools, and the existential pressure to restore and protect nature, open up unprecedented opportunities for more decentralized, cooperative systems that allow money to chase overall value-creation, rather than the profits of a select few.

Smaller scale actors will start to use technology in new ways—not necessarily to industrialize the land itself, but to better inform their choices for how land is managed, so attendant and peripheral vital ecosystems are not degraded, watersheds remain robust and resilient, and overall production of climate-resilient, sustainaby sourced foods, can expand and be better rewarded.

Navigating in seven dimensions—the polycrisis

We describe the polycrisis as a wicked problem, because each of its drivers makes it harder to reduce the risk and cost associated with the others. There are at least five major threads to the ongoing polycrisis, each of which continues to constitute major disruption, even if time-sensitive causes, like the COVID-19 pandemic, would appear to have subsided. Crosscutting concerns mean at least seven dimensions of interacting crisis are making solutions more elusive:

Climate disruption is contributing to nature loss and biodiversity collapse, reducing ecosystem health and resilience, depleting watersheds, and dislocating or devastating critical attendant species, including but not limited to pollinators.

The COVID-19 pandemic not only disrupted supply chains and livelihoods, it also degraded trust between key partners, both within countries and internationally; building back required major shock investments, which are causing their own ripple effects.

Conflict: The World Food Programme reports: "Conflict is the main driver of hunger in most of the world’s food crises, from Sudan to Syria, from Yemen to the Democratic Republic of the Congo, pushing food and nutrition insecurity to historic levels. A sharp escalation of conflict in Palestine has seen hunger levels soar there also." Russia's invasion of Ukraine, in February 2022, sent shockwaves through food systems, and effectively weaponized global grain supplies; the effect on commodities, including not only food, but also fuel, has led to reduced cooperation and what some see as an existential threat to major development assistance.

Protectionist measures are spreading, and trade is becoming more unilateral and bilateral, reducing the benefits and feasability of multilateral arrangements; this makes it harder to ensure sufficient food supplies can circulate, globally.

Meanwhile, all of these have impacted incomes, with the wealthiest increasing their incomes substantially while most people have seen opportunity and income stagnate or decline. This situation may be worsened by the labor market effects of emergent "generative AI" technologies.

The polycrisis necessitates a cross-cutting approach to thorny problems in both everyday operations and at the macro level. This is another complication, because it is so difficult to align local actors immediate responses with governments' efforts to align policies, incentives, and macro-scale systems with future success.

All of these stresses also coincide with worsening stresses on public budgets, including in the wealthiest countries. Fiscal space is becoming a major priority, which is worsening stresses related to protectionism, incomes, and value chains.

Each of these threats to human safety and thriving can be countered with sustainable food systems activities. Since the last stocktake on Food Systems Summit progress, the Food System Economics Commission (FSEC) produced a flagship global policy report, the first true integrated assessment of the overall costs of food systems throughout the world. The FSEC report shows that since April 2016, when the Paris Agreement was signed, unsustainable food systems have cost $142.3 trillion.

As these stresses play out and compound each other's effects, innovators, practitioners, and policy-makers, must now work to find entry points for resilience-building investment that supports sustainable activities and reduces polycrisis risk. Institutions are not, generally, built to favor investments that deliver technology, capital, and market reach to low-income, marginal communities, but this must happen, if we are to maximize the benefits of health-building, sustainable food systems.

Transformative potential is waiting to be unlocked

If incumbent industries and dominant market players were the best way to achieve systemic transformation, it would have happened already through the prevailing logic of their business models. Regardless, we have to acknowledge:

Industrial agriculture depletes soil fertility and future fresh water availability, while degrading ecosystems and threatening pollinator populations that are crucial to agriculture.

Industrial systems also contribute to climate change, both through energy-based global heating emissions and through the effects of land clearing and other extractive land use activities.

The observed preference among vertically integrated agribusiness conglomerates for income from sale of inputs to farmers means market dynamics have been structured to reduce margins for producers while transferring agricultural capital to faraway interests.

Rethinking what success looks like can open up new areas of value creation, jump start cooperative investment strategies, and refocus on the foundational value of on-farm assets, including healthy soils, abundant fresh water, vibrant ecosystems, and resilience against extreme weather events.

Financial services, including insurance—whether underwritten entirely by the private sector or wholly or partially by the public or multilateral sectors, or through farmer cooperatives—should account for such on-farm assets and their wider resilience value. Agroecological resilience value can equate to enhanced fiscal stability and improved investability of local small-scale economies, which can in turn lead to the diversification of economic activity in vulnerable and frontline communities.

Earth system data is essential for expanded value creation

To build agroecological resilience value, including in vulnerable and remote communities and across networks of smallholder farmers, it is essential to make Earth system data available to more people, in more usable forms. Whether small-scale farmers access and apply Earth system data themselves, or whether they interact with an emerging system of small-scale intermediaries, who deliver independent and verifiable science-based monitoring of nature and climate outcomes, Earth system insights can create vast new opportunities for public, private, multilateral, and cooperative investment in sustainable food systems.

Such data are much more than reference material; they provide actionable insights, verifiability, and an incentive to compete for impact-focused investment. They have the potential to create new local economies of scale for climate-smart agriculture, and to create new efficiencies for building on-farm assets and more resilient regional economies, while supporting action toward climate goals and across the 17 Sustainable Development Goals.

In some communities, Earth system data may focus on soil ecology and carbon sequestration capacity; in others, water resources might be the primary focus; some will specialize in restoring ecosystems vital to the efficient production of a particular indigenous crop variety. Many communities will find they are best positioned to maximize sustainable agriculture investment potential if they are able to deliver benefits across a variety of overlapping nature, climate, and health benefits.

Planetary health is everyone's business

While we must focus on the need to deliver planetary health benefits through farming practices, and on delivering scientific and sustainable practice capacity to vulnerable and underserved communities, it is also the case that large-scale financial actors, and entire nations, need to understand their own impact on and vulnerability to risks related to planetary health.

The recent advisory opinion from the International Court of Justice on the responsibility of states to act to reduce global climate-related risk makes clear: All nations have a legal duty to act on climate, founded not only in the United Nations Climate Convention and other treaties, but on customary international law and in transcendent human rights. Nations can hold each other accountable for shirking this legal obligation, and so increasingly, we will see nations using planetary health insights to shape their relations with other nations.

The ICJ climate opinion also linked the legal duty to act on climate to the health of the marine environment and legal obligations to be good stewards of the global ocean. This means food systems innovation, incentives, and investments, should prioritize practices that reduce pollution of watersheds and marine ecosystems, support protection of marine biodiversity and wildlife, and reduce the impact of global heating emissions not only on farmlands and mountain glaciers, but on the composition and thermal dynamcis of the ocean as well.

Nations need to know whether they are building or eroding macrocritical resilience value, both within their borders and throughout the world, and for the first time, there is clear legal guidance that the whole biosphere is part of that responsibility. As resilience value becomes more discernible, mainstream, and investable, even the largest banks will need to fend off competition from more efficient smaller scale competitors. It is simple arithmetic: If it is clearly visible that a given action destroys more value than it creates, it will lose favor, even among the most profit-focused investors.

Governments and institutional investors may start the rush, but there will be a rush to demonstrate enhanced climate risk reduction and resilience value alongside financial value. Agriculture provides an essential tool for making this possible, and small-scale actors, when properly incentivized and coordinated, are the most investable path to early planetary health benefits.

We must not, however, repeat the mistake of forcing an unmanageable and corrosive level of risk onto family farms, rural communities, and the most vulnerable. This is a systemic inefficiency which also undermines trust, as it embodies a lack of ethical decision-making.

Instead, new cooperative financial structures need to prioritize the delivery of value to small farmers and local communities. Once large-scale system-shaping operators, like governments and major banks, know how to assess, compare, and support far-reaching resilience value benefits, the foundational value of stable value on small farms and in local communities will be more apparent and more investable.

Conclusion

Climate Civics and the Climate Action and Food System Alliance see our moment, in mid-2025, as a turning point in world history. We have the new, emerging insights, organizational tools, financial innovation, and communications technologies available to ensure we get the best information to everyone. We understand, better than ever before, how human activities impact planetary health, and we can clearly and directly incentivize investments in sustainable food systems that enhance the health and resilience of both people and nature.

At the same time, devastation and disruption of nature and of Earth's climate system are continuing, at this hour, to worsen. We are running out of time to put the brakes on a decades-long inadvertent project of pointless destruction, and that time crunch may eventually hit all market actors, whether they are paying attention to climate and nature-related value or not.

Food systems are one of the best, most actionable ways to move new flows of sustainable capital into local economies and to improve overall sustainable development outcomes and reduce systemic risks to the macroeconomy. Leveraging lightweight, digital technologies to deliver Earth system insights and track co-benefits, can create conditions for the most significant boom in value-building finance, changing the game to the point where the wealthiest institutions compete to support asset-building in the poorest communities.

The wealth of nations can be, should be rooted in the health of nature. Food systems are the tool for getting us there.